However, once you overcome your fears and take the courageous step forward, you will find great realizations, enjoyment, and stronger bonds between family members.

We spoke with Hiromi Kishida, a wheelchair user who works at Mirairo Inc. as a universal design consultant and training instructor for "universal manners," and her daughter Nami, who works in the company's business promotion department, about their mother-daughter trip to New York.

Text: Hiromi Kishida

*This article will be published in two parts.

Part 2 (Article by Nami Kishida)

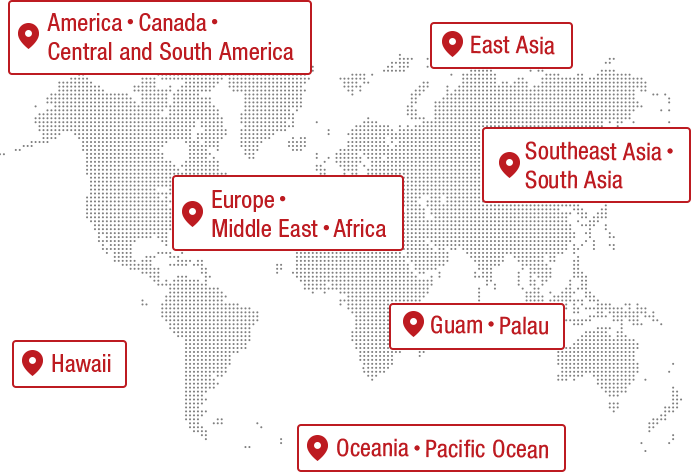

Admiration for New York, the city of diversity

The reason I chose New York as a travel destination is because I have always admired it. It is the birthplace of all trends, full of challenges and dreams, and a city that never sleeps... I had such a glittering image of it. However, my vague admiration for New York turned into a determination to "go, see, and learn!" when I visited Hawaii in 2015. Hawaii was the first foreign country I visited since I started living in a wheelchair, and although I was full of anxiety at the time, it was a powerful experience. The natural way people interact with people with disabilities due to the Aloha spirit, and the experience of being able to enter the beach in my wheelchair, gave me confidence in life.

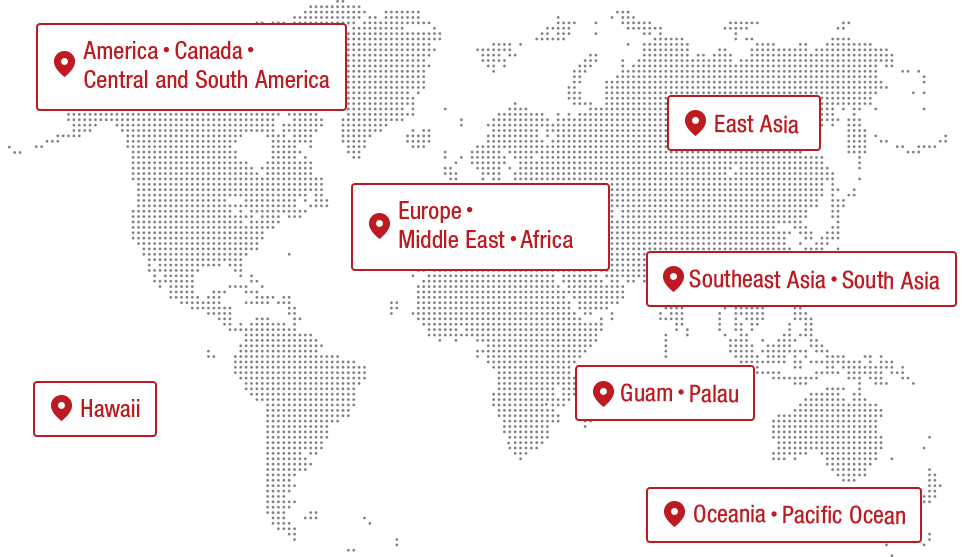

However, Hawaii is one of the world's leading tourist destinations. I saw many facilities and services for tourists who are staying temporarily, so next time I wanted to see a city where I could imagine "working and living there". New York is a city of diversity, isn't it? The differences in nationality, ethnicity, culture, and language of the people passing by are incomparable to those in Japan. I learned how people with many differences, including people with disabilities, live together in New York, and I wanted my daughter and I to convey this to Japan, where diversity will continue to increase in the future.

A wooden wheelchair to warm you up before your flight

I was very nervous about traveling by plane. I always feel nervous when I try a new mode of transportation or route, not just planes. I can't sleep the night before. What worried me this time was the length of the flight. I had never flown for 13 hours, so I was worried about whether I could use the restroom and get bed sores. Since I was with my daughter, I felt relieved that she would be able to help me without hesitation if anything happened, but I also felt a little anxious. I kept thinking, what if I ruined my daughter's fun travel mood because of me, what if I made her feel awkward? Maybe I was timid because I didn't want to fail on this trip with someone important to me!

That's why I was nervous right up until the moment I got on the plane, but when I saw the cute wheelchair that was prepared for me at the boarding gate, my tension eased a little. When I saw the wooden, round, curved shape, I couldn't help but exclaim, "This is cute!" Metal wheelchairs have a cold look to them, and somehow make you feel like you're being assisted. When I uploaded a photo to social media, other wheelchair users also praised it, saying how cute it was. I received a lot of comments, like "Have fun!" and "Take care!", and I felt a little more relaxed at the time.

I was in a wooden wheelchair and was the first to board the plane through the pre-boarding gates.

The kindness that accompanied me on my 13-hour overseas flight

I have paralysis of the lower body and have no feeling below my belly button, so I am prone to developing bed sores. I was able to prevent bed sores by turning over in my seat and placing a cushion provided on board under my body. I was worried about using the restroom, but I used it twice during the flight and didn't have any trouble. When I used the restroom, I asked the flight attendant to help me transfer to the onboard wheelchair and she supported me until I entered the private room in my wheelchair. I was also relieved that I was given a seat closest to the spacious restroom (multipurpose toilet).

Wheelchair accessible toilets on board

Not only was I relieved by the barrier-free facilities, but what was even more reassuring was the thoughtfulness of the flight attendants and airport staff. When I transfer from my own wheelchair to the in-flight wheelchair, I always have two people lift me up. There is a way to hold me that puts less strain on the body, and in my case, it is easier if they hold me under my arms and around my knees. Once I explained the comfortable way to hold me, the check-in counter staff passed it on to the gate staff, and the gate staff passed it on to the flight attendants, and everyone helped me with the comfortable way to hold me. I was surprised because they treated me the same way at the airport in New York. I was very happy to have an atmosphere where I could boldly ask for advice about things that were difficult to explain.

If I go out more in a wheelchair, society will get used to it.

I realized that if I muster the courage to go out, I will meet and have more opportunities to talk with people who can support me wherever I go, whether it's on a train, bullet train, airplane, or ship. It also gives me more opportunities to communicate the support I need, and it also gives station staff and flight attendants more opportunities to get used to supporting me. This time too, communication with the flight attendant was smoother on the return flight than on the way there, and I was very happy to see such a small change. I think that if people with disabilities who are hesitant to go out were to take the plunge and try to go out more and more, it could ultimately lead to a society where it is easier for them to go out.

A wheelchair-friendly New York sightseeing tour

Just looking at the cityscape from afar from the window of the car driving on the highway made both my daughter and I excited. The bridge over the river, the building where retro brickwork and modern architecture are mixed, the towering buildings, the neon signs so bright that you would think it was daytime even in the middle of the night, and the diversity of the people passing by. It was just like I saw in the movies. I felt a big surge in my heart that I was in my dream city of New York. I laughed with my daughter and said, "So this is what it means to be excited even in a wheelchair."

On the first day, we visited art museums and theaters. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I was simply overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the exhibits, including their size, number, historical depth, and density. But apart from the artworks, there was one thing I liked more than the artworks. There was a space exhibiting a huge stone gate from ancient Egypt, and the structure was such that you could enter the inside of the gate by stairs, but the wheelchair lift that was installed there was made to look just like the heavy stone of the gate. It was so realistic that I didn't realize it was a lift at first. It was a very stylish presentation.

At the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I was surprised at how close I was to famous masterpieces such as "Van Gogh's Self-Portrait" and "Monet's Water Lilies." Most of the works had no partitions or showcases, so I was able to appreciate them at eye level without any problems, even though I'm in a wheelchair.

The Broadway musical "FROZEN" was also a showy production, and the audience's reaction was fun, with loud cheers and roars, unlike in Japan. The audience was so powerful that I couldn't move from my seat for a while after the show. It was clear to see that it is the center of entertainment.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art's wheelchair and stroller-accessible entrance

Japan is by far the most advanced country when it comes to barrier-free facilities

After seeing the magnificent works of art, I felt a little calmer as I walked through the streets of New York, and in the midst of the glittering, dreamlike space, I could see the reality. In terms of barrier-free roads and facilities, I feel that Japan is by far more advanced. In Tokyo, most of the main roads are paved with concrete, so I didn't feel much inconvenience. However, the streets in New York are full of bumps and cracks, and they shake when you run in a wheelchair. My daughter was always in sneakers because she was worried that the heels of her pumps would get caught and she would fall. There are many puddles and narrow roads due to construction work, so it takes a lot of strength and courage to push a wheelchair out into the city by yourself. In fact, during my five-day stay, I rarely saw any wheelchair users going out alone. In Tokyo, I would see at least two a day.

Japan is by far the most advanced when it comes to barrier-free subways. In New York, about 50% of subway stations have elevators, but most of them are out of order and not working. The LCD display on the platform shows "stations where elevators are not available" in real time, and I had to smirk at the long line of "out of order" signs. Repairmen don't come on weekends, so there's no prospect of them being fixed. Over 98% of Tokyo stations are equipped with elevators and escalators, and they rarely break down, so the difference is clear.

In New York, there are no wide passageways for wheelchairs or strollers like those found in Japanese stations, and no automated ticket gates. Instead, there are emergency doors made of bars that you can use to enter and exit. When you open the door, a siren goes off, making it a very loud noise and drawing attention to you. It's a bit embarrassing.

Not only the facilities, but also the service is different from Japan. I passed through about three stations in New York, but I never met a station staff member. Apparently they are rarely on duty. However, there is no gap between the platform and the train, so I was able to board the train on my own without the assistance of a station staff member. I thought it was really amazing that Japanese train companies escorted me to the platform, provided a ramp, and carefully handled my transfer and contacted my destination.

It is possible to get on and off without placing a ramp.

Many unmanned stations in the New York subway

The entrances to shops are mostly manual swing doors or revolving doors that are difficult to open while in a wheelchair, whereas in Japan, convenient automatic doors are the norm.

Even if it is inconvenient, I don't feel like I'm being restricted

Compared to Japan, New York City is not barrier-free, but even though I felt inconvenienced, I did not feel restricted. This is because the people of New York (New Yorkers) walking down the street had no barriers in their hearts.

At first, I wondered if New Yorkers were indifferent to others. On the first day, I went to a supermarket and a fast food restaurant, but the cashiers were fiddling with their smartphones while they were cashing out, and they put my bags on the counter at a height that was hard to reach. They never even smiled or said "Welcome." I was used to Japanese service, so I couldn't help but feel uncomfortable.

My impression changed on the third day of my stay, when I went to see a concert at a theater in Times Square. The seating was standing-only, and there were no wheelchair seats, so my daughter and I waited at the back of the hall. As more and more people came in, I couldn't see the stage at all because I was at a low eye level. Just as I was about to give up, thinking that there was nothing I could do, someone called out to us in Japanese. It was a Japanese person who had been living in New York for a long time.

"You can't see the stage from up there, can you? Let's ask the people around you to let us go to the front! You've come all the way here, so you'd be missing out if you don't enjoy yourself."

"but……"

"If you want to go to the front, you have to say it clearly yourself! If you don't say you want to see the stage, nobody will understand. And New Yorkers are very open-minded, so they'll say, sure."

When I said that, the person said "Excuse us!" and pushed his way through the crowd to lead us out. Contrary to my surprise, the people in front of me said "Of course!" and made way for us one by one. No one looked annoyed. It was a shocking night in many ways.

Not just "deciding the rules" but "facing the person in front of you"

It was also striking that the operations of the store staff and attendants (procedures for entering and using the facility, methods of assistance, etc.) were not clearly defined. Even in the same facility and in the same position, different people responded completely differently.

For example, on a route bus. When I get on in a wheelchair, the driver secures my wheelchair with a belt, but the place and method of securing it vary. Some drivers tell the other passengers, "Wait, we're going to pick up the wheelchair!", while others just secure it quickly. Some people might think this is "rough," but strangely enough, I felt comfortable with their "flexibility" at the time. This is because they didn't respond mechanically according to rules and regulations, but instead placed importance on the relationship and communication with me. If I could clearly explain in my own words why I was in trouble and how I wanted help, they would think about it together with me.

Buses are also safe to use

It's not like they do it because you have a disability or because it's a rule. It's like they do it because you are them. I was happy with that feeling. Of course, some people were rude to me, but I was able to take it in a positive way, thinking, "Maybe my explanation wasn't good. Next time, I'll ask someone else!"

Ferry to the Statue of Liberty

Taking a courageous journey expands your freedom of choice

We took a sightseeing boat to Liberty Island to see the Statue of Liberty. A New Yorker told us that taking a photo behind the Statue of Liberty is proof that we have landed on Liberty Island, so my daughter and I took a photo imitating the Statue of Liberty. This is one of my favorite photos.

While listening to the audio guide, I thought about the many meanings of the word freedom. Having the freedom to live your own way means having the freedom to make your own choices. You can't wait for it to be given to you, but you have to step out with courage and grab it. Just because you have a disability doesn't mean you're silently treated differently. New York was full of such freedom and challenges.

Japan and America. Not only are the barrier-free aspects of hardware different, but the barrier-free aspects of hearts are also completely different. There are good and bad points. I learned that I have the freedom to choose which place I feel more comfortable in.

Ten years ago, when I was told that I would be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life due to an illness, everything went dark. My daughter and I cried until our tears dried up. When we went out into the city, we encountered various barriers and felt like we were being stared at by people around us, and it was hard to live. My daughter also always felt guilty. But her stay in New York, her experiences of constantly sharing her feelings with those around her, stepping out into new places, and seeing exciting scenery made her feel that "being disabled is not something to feel guilty about, nor is it something that needs to be protected."

View of New York from Rockefeller Center

I've come to feel proud that I live in Japan, where there are many automatic doors and elevators, where the staff on trains and airplanes provide solid support, and where I even feel polite hospitality. However, even if I ever feel "hardship" in the future, I have many options. Now, I have the option of taking the plunge and living in New York.

If there are no options, there is no choice. If there are people out there who, like me, have a disability that makes life difficult or makes them feel like giving up, I would encourage them to go on a trip. The realizations, emotions, troubles, and encounters with people you have on your travels - all these experiences will increase your options in life. It takes courage to convey that you need support, but if you take the plunge, it will actually work out, and I will never forget the joy I felt when my message was conveyed.

That 13-hour flight became the wings of courage that expanded the freedom of my life.

Hiromi Kishida

Born in Osaka in 1968. After giving birth to her eldest son who had an intellectual disability and experiencing the sudden death of her husband, she herself became paralyzed from the waist down due to the aftereffects of an aortic dissection in 2008. In despair after undergoing rehabilitation for about two years, she decided to commit suicide, but a comment from her daughter prompted her to join Mirairo Inc., where her daughter was one of the founding members. She gives an average of more than 150 lectures and training sessions per year. She has served on numerous review committees on barrier-free access and education for children with disabilities for the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the Japan Tourism Agency and others. Her books include "Mama, If You Want to Die, It's Okay to Die" (Chichi Publishing).

The contents published are accurate at the time of publication and are subject to change.